Dominae and fashion: the Flavian matrons

At the end of the civil war between 68 and 69 AD, which broke out after Nero’s death, the empire passed into the hands of Vespasian, who re-established the balance lost with the end of the Julio-Claudian dynasty. A man of brilliant military abilities, Vespasian was particularly attentive to financial matters and officially ratified the powers of the emperor through the Lex de imperio Vespasiani. Among the aspects that differed the Flavian dynasty from the previous one, there was certainly the lesser visibility of its matrons; except for Domitia Longina, the other women in the family took on a more reserved profile, being defined “invisibles”, perhaps due to their short time at the top of power.

This was already evident about Flavia Domitilla, Vespasian’s wife, and Titus and Domitian’s mother. The little information about her comes to us from Suetonius, according to which she obtained roman citizenship starting from the latin status thanks to her father Flavius Liberalis. Furthermore, she would have been the lover of the roman knight Statilius Capella before marrying the future emperor, but she would have died before Vespasian’s accession to the throne. Beyond the new hypotheses of scholars on her origins, Flavia Domitilla undoubtedly represents greater social mobility during the first century AD, like Antonia Caenis, Vespasian’s lover before marriage and after the death of his wife. Suetonius claimed how the princeps held Caenis in high regard: the freedwoman of Antonia Minor previously contributed to foiling Sejanus’ conspiracy against Tiberius.

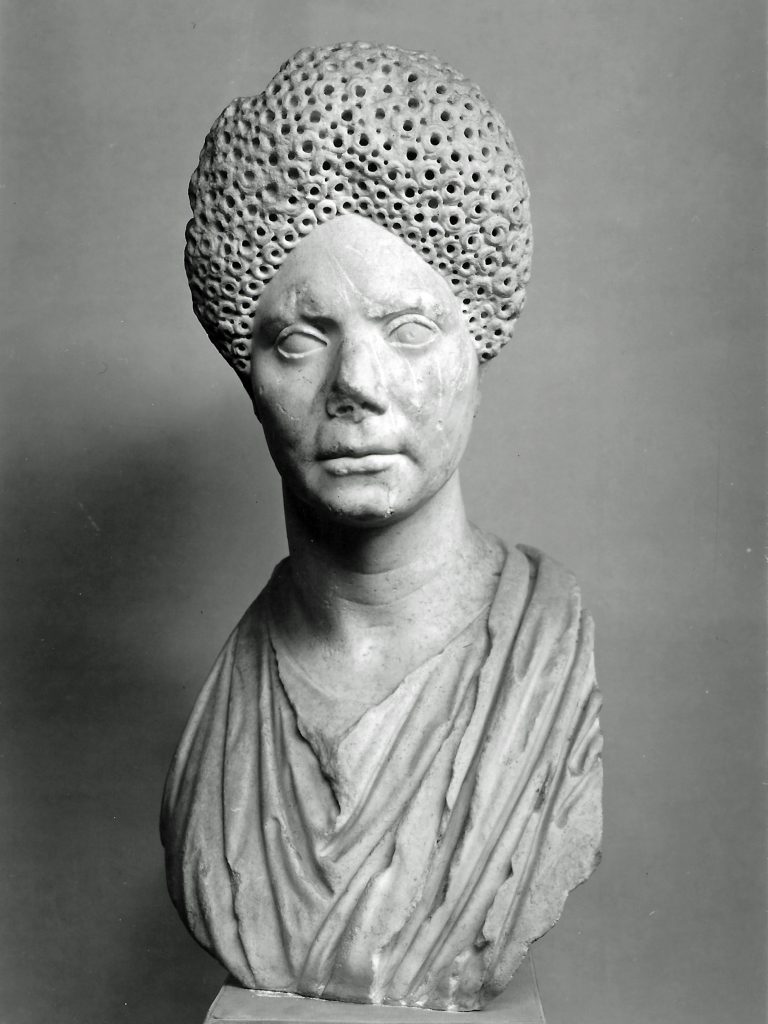

Private portrait of a Flavian lady (1st century AD) – Currently exhibited at Palazzo Grimani.

As for Titus, in 63 AD he married Arrecina Tertulla, the daughter of Marcus Arrecinus Clemens, with whom he had Julia Flavia. After about a year, Arrecina’s death convinced Titus to marry Marcia Furnilla, belonging to a senatorial family and niece of Quintus Marcius Barea Soranus. When he fell out of favor under Nero, Titus hastened to divorce his wife to avoid involvement in 66 AD. According to Cassius Dio, his only daughter Julia would have had a relationship with his uncle Domitian, who had married Domitia Longina. She was the daughter of Gnaeus Domitius Corbulo and Longina, relative of Julio-Claudians: becoming Domitian’s wife in 70 AD after being forced to divorce she seal a union that was also politically strategic. Once emperor, Domitian conferred to Domitia the title of Augusta, which she retained until her death, despite some scandals. In addition to the rivalry with her niece Julia, Domitia would have had a relationship with the actor Paris punished with a temporary divorce from the princeps. Once she returned, she demonstrated her qualities as a roman matron, and her personal prestige allowed her to survive the killing of Domitian in 96 AD, of which she would have been an accomplice. Honored and respected by the Antonine emperors too, Domitia died between 126 and 128 AD, but without being deified.

Private portrait of a Flavian lady (1st century AD) – Room X of the National Archaeological Museum of Venice.

Paradoxically, the poor visibility of Flavian matrons has a totally opposite iconographic counterpart, because their images are characterized by flashiness, especially regarding hairstyles. An example comes from two portraits of the Grimani collection.

In the first, what stands out above all is the high, honeycomb-shaped hair on the forehead (reproduced with a drill), which on the nape takes on a helix shape with the bun to collect the various braids. In the second, there are some real curls (anuli) falling on the upper part of the face. Both are private representations despite the attribution hypotheses to the women of the imperial family, which testify to the realism of portraiture of the time: the hairstyles highlight the physiognomy of the faces, which transmit austerity and intensity, pointing out, for example, the advanced age of the second subject.

The skill of the artists allowed the creation of soft surfaces for the hair thanks to the volume and chiaroscuro effects. But in reality, creating this hairstyle named orbis and being able to increase female height required some experience for its difficulty, for using pins, hairpieces and nets that supported it, according to a fashion adopted by the aristocrats of the period whose transformations communicate the succession of the dynasties. Thinking of Flavia Domitilla’s portraits, they link the Neronian era to that of the Flavians given the presence of disc curls over the temples, the central parting and the tail gathered on the neck. Julia Flavia’s portraits instead show the typical dynastic hairstyle, with a diadem of curls on her forehead and a knot on the back of the neck tied with a pin.

Progressively, the hair became more voluminous and complex, symbolizing the pomp of the Domitian court and perhaps inspired by the curls of the theatre masks. Domitia Longina initially managed to stand out both for her personality and for the nature of her hair: being particularly curly, they allowed her less backcombed hairstyles and more braids. She would later adopt a less alternative hairstyle, but in later life she managed to influence the Antonine augustae too, with hairstyles developed more vertically, serving a trait d’union role not only politically but also from a stylistic point of view.

Michele Gatto

Bibliography

Alexandridis A. 2020, Portraiture of flavian imperial women, in E.D. Carney, S. Müller (ed. by), The Routledge Companion to Women and Monarchy in the Ancient Mediterranean World, London, pp. 423-438.

Buccino L. 2011, “Morbidi capelli e acconciature sempre diverse”. Linee evolutive delle pettinature femminili nei ritratti scultorei dal secondo triumvirato all’età costantiniana, in E. La Rocca, C. Parisi Presicce, A. Lo Monaco (a cura di), Ritratti. Le tante facce del potere (catalogo della mostra, Roma, Musei Capitolini, 10 marzo – 25 settembre 2011), Roma 2011, pp. 360-383.

Fraser T.E. 2015, Domitia Longina: an underestimated augusta (c. 53-126/8), in “Ancient Society” 45, pp. 205-266.

Galimberti A. 2016, The Emperor Domitian, in A. Zissos (ed. by), A companion to the flavian age of imperial Rome, Chichester, pp. 109-128.

La Monaca V. 2013, Flavia Domitilla as delicata: a new interpretation of Suetonius, Vesp. 3, in “Ancient Society” 43, pp. 191-212.

Murison C.L. 2016, The Emperor Titus, in A. Zissos (ed. by), A companion to the flavian age of imperial Rome, Chichester, pp. 109-128.

Paoli U.E. 2017, Vita romana. Usi, costumi, istituzioni, tradizioni, Milano.

Traversari G. 1968 (a cura di), Museo Archeologico di Venezia: i ritratti, Roma.

Van Abbema L.K. 2016, Women in Flavian Rome, in A. Zissos (ed. by), A companion to the flavian age of imperial Rome, Chichester, pp. 109-128.