Stories of St. Mark’s Square

About re-uses and ancient inscriptions

«The marble columns of the belfry are mixed everywhere, falling, together with the cornices, the attic sculptures, and the heavy roof of the spire. The boulders stood at the corner of the Basilica, and the column, which was torn up, cushioned the blow. They tore open the side of the Marcian library towards noon». Thus the archaeologist Giacomo Boni, who rushed to the disaster site two days after that tragic July 14, 1902, described the scene before his eyes. The St. Mark bell tower had crashed, giving way to a pile of rubble.

Today, Stories of St. Mark Square will speak about ancient inscriptions and their reuse.

A few years after that terrible catastrophe, in May 1905, during the consolidation works of the foundations of the bell tower necessary for its reconstruction, a Roman funerary stele was discovered, inserted in the fourth step of its base. Obtained from a block of Verona limestone, the tombstone lacked the lower part; only nine lines of the text remained. The inscription, now preserved in the cloister of S. Apollonia, dates back to the beginning of the 1st century A.D. It marked the burial place of Lucio Ancario, son of Caio. A Roman citizen enrolled in the Romilia tribe who had held important military, civil, and religious positions in the colony of Ateste.

Gherardo Ghirardini, Superintendent of Antiquities of the Veneto, studied the find, considering this archaeological discovery extraordinary. Until then, they believed ancient stones and bricks used in Venice as building materials came from cities close to the estuary, such as Altino, Oderzo, Aquileia, and the Dalmatian coasts. Surprisingly, the Ancario inscription proved instead that the Venetians had procured ancient materials to be used in the building from inside mainland Veneto, and in a very early period as for the construction of the first St. Mark bell tower at the end of the 10th century.

Ghirardini hypothesized that the sepulchral stone had arrived in the lagoon from Este following the same path as the trachyte of the Euganean Hills, widely used in the same foundations of the bell tower. He then concluded his essay by observing that the inscription and the name of Ancario would have disappeared forever had it not been for the ruin of the bell tower.

The singularity of the find lay in its place of origin. Certainly not in the fact of its use as a building material. Despite not having risen over a previous ancient settlement like other Italian urban centres of medieval and modern times, Venice, together with the islands of its lagoon, boasts a considerable presence of ancient artefacts recycled over the centuries. We can calculate that the epigraphic reuse in the area of the Venetian lagoon exceeds 150 units. These inscriptions, many dispersed now, were used in the construction – invisible like the stele of the Atestine magistrate or put in place on sight, preferably along the canals – of buildings and infrastructures of different types: banks, piers, bridges, wells.

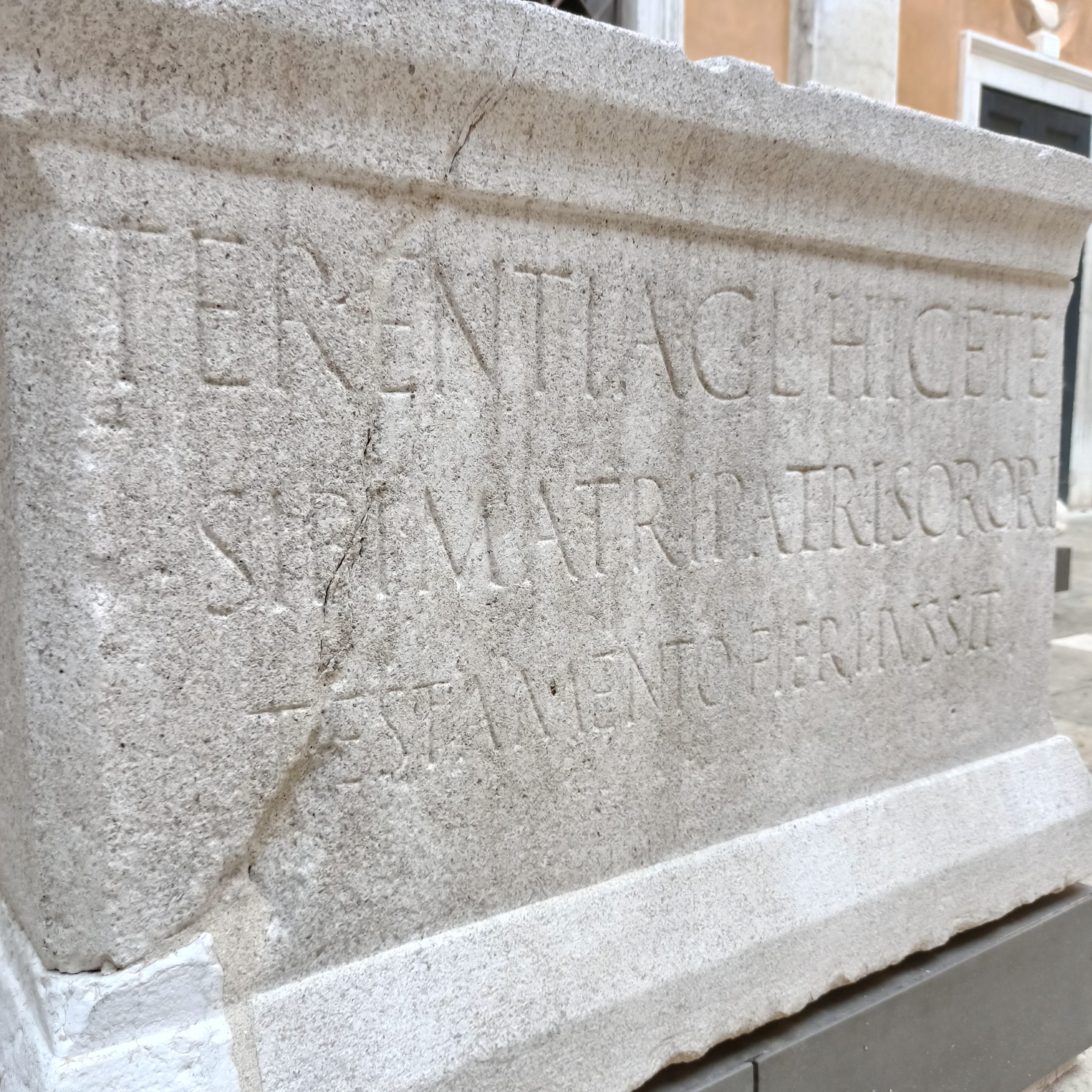

Almost all of the oldest Venetian wellheads came from reworking statue bases, column drums, votive or funerary altars, and ancient cinerary urns. It is the case, for example, of a cinerary box urn kept in the courtyard of the National Archaeological Museum of Venice. The artifact in Aurisina limestone, used as a well at San Trovaso as early as the 2nd half of the 15th century, bears two inscriptions in a kind of remote dialogue between women. On the front side is remembered the freedwoman Terenzia Hicete, who in her will ordered the execution of the funerary monument for herself, her mother, father, and sister. The name that appears in the inscription, dated within the 1st half of the 1st century A.D., was widespread in the Roman world and Altino; the surname of the deceased is perhaps of Greek origin.

Equally interesting is the second, more recent inscription engraved on one of the side faces. The text documents the transfer of the well to the Benedictine monastery of Ognissanti, which took place in 1518 at the time of the abbess Pacifica Barbarigo, «in tempo de madre superiora Pacifica abbatesa.» In short, from Terenzia to Pacifica.

Ancient sarcophagi were also often used to accommodate new burials. The practice, already attested in the late Roman period, continued in the Middle Ages and, in Venetian territory, even beyond. In this regard, we recall a coffin in Istrian stone, now in the Archaeological Museum, which testifies to a rare story of conjugal love, or maybe two. In the 1st half of the 15th century, it was in Pola in the church of San Mena. Then, the monument was transferred to Venice and used around 1563 in the church of San Polo as the burial of Francesco Soranzo and Chiara Cappello.

The new lid, made on that occasion, bore an epitaph that defines the woman as a «very loving wife». But someone else preceded the Venetian married couple in the same tomb. The spouses Marco Aurelio Eutyches and Aurelia Rufena rested there together around the middle of the 3rd century A.D. after having lived for a long time «sine ulla querella». Maybe, the reuse and second inscription are not accidental at all.

You can learn more about these and other stories on July 28. We will welcome Lorenzo Calvelli from the University of Venice as part of the cycle of informal meetings in the historic courtyard of the National Archaeological Museum of Venice, entitled Stories of St. Mark’s Square. The professor will talk about the epigraphic reuse in Venice and guide those who want to try deciphering the ancient inscriptions displayed in the courtyard.

MDP

For quotes and insights:

G. Boni, Costruzioni e macerie, in Il campanile di San Marco riedificato. Studi, ricerche, relazioni, Venezia 1912, p. 52; L. Calvelli, Il reimpiego epigrafico a Venezia: i materiali provenienti dal campanile di San Marco, in “Antichità Alto Adriatiche” 74, 2013, pp. 179-202; L. Calvelli, Iscrizioni esposte in contesti di reimpiego: l’esempio veneziano, in L’iscrizione esposta, Atti del Convegno Borghesi 2015, a cura di A. Donati, Faenza 2016, pp. 457-490.

Thursday 28 July, 10.30 am

Piazzetta San Marco, 17

L. Calvelli – From the Piazza to the Museum: reuse of inscriptions and epigraphic storytelling

Reservations on 041 29 67 663